Watching the Moon Explode (Together)

- R. S. Williams

- Jan 31, 2022

- 5 min read

By R. S. Williams

I don’t know anything about Cuba. But I did go to the trouble of asking you what to write about. I know that you love it, not because you are from there but because you know a lot about it. I know how you always pronounce it without that invisible y, coob-ah, rhymes with tuba. You say it with the exclamation point at the end and the beginning, your whole mouth forming around the word, your lips peeling back as you twist your hands in joy. When we both returned from the summer I let you take me through the museum. You guided me through the Cuba exhibit, told me about the bee hummingbird, which is the smallest bird in the world. Endemic to Cuba. That’s the only thing I remember about it now. That jewel-sized hummingbird that can’t be found anywhere else.

It’s called the island rule. Isolated for long enough, large species get larger, small species get smaller. It’s not really a rule, just a suggestion. All across this world, little pockets of creatures striding away from each other. Bee-sized hummingbirds. Giant snakes, their teeth but blades, poison lying dormant in their genes. Capybaras and tiny spiders.

I don’t know about those hummingbirds, but bees are never lonely—they evolved of one mind. It’s called eusocial. We are social creatures, but without the eu. What’s the difference? The removal of fanged dentures. I suppose it means I love bad literary analysis, the kind where you try to divine what exactly the author meant to say. I suppose it means I watch multiple performances by the same actor, different characters embodied by the same person, to try and catch a glimpse of something solid. I asked you if relationships were just friends who you fuck. You thought there was something deeper, a reservoir to tap into beneath all I already feel for you. I told you as much. That we stand on bedrock. Lingering in the air between us, then, was the unnamed knowledge that I would kiss you if you asked, of course I would. I wouldn’t do it as a favor, nor to simply feel the press of your lips: a kiss is always a shadow; I’d kiss anyone before I’d tell them the plain truth. I’d straddle your lap and jam my tongue down your throat, make you believe me. And I’d lean back and look you in the eye and wonder if I’ve ever really loved you at all.

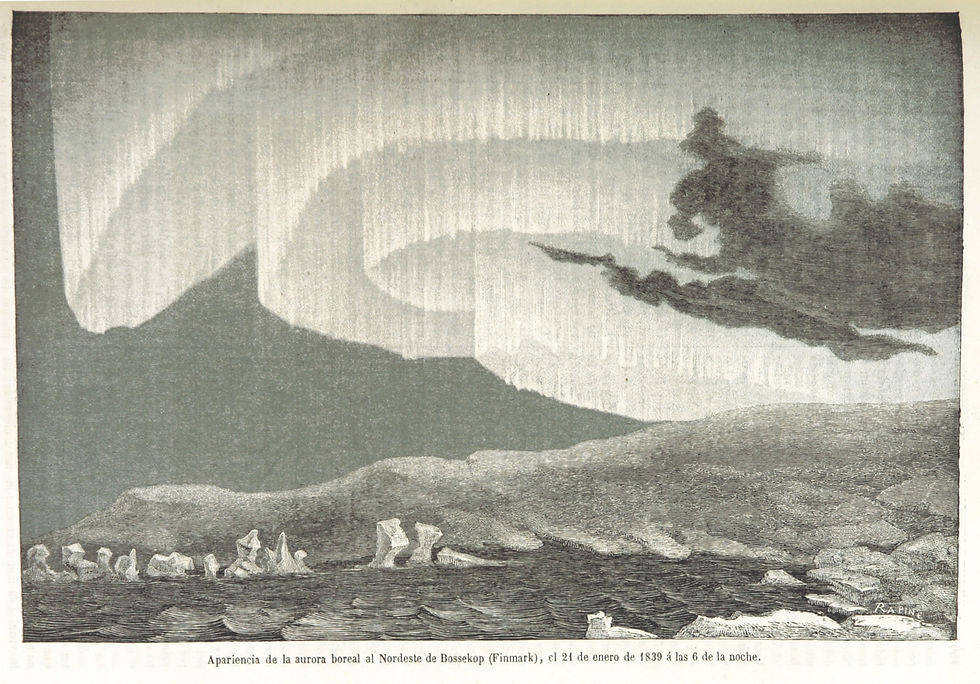

In 1178, five monks had their eyes set on the moon, on its silvered horns, and watched its tip split in two. Five monks watched the lip of the moon peel in half. Don’t mistake my sentimentality: when the moon shatters, its millions of pieces are the same as if they were one big piece; there is nothing dead, nothing new alive. There is no center in which the heart of that tract resides. I snag on it because there was no one to take those men in hand, offer them an explanation as a red glow spread in a glowing circlet. Their bodies must have been sick with it. Have you ever felt anything so pure and true as a piece of the moon exploding before your eyes? You haven’t. You can watch Saturn through a telescope all you like and you’ll never be that futile. You’re never going to do pushups on top of a spider’s web; you’re never going to have your brain turned into a beehive; God’s never going to talk to you in a language made of circles while you stand on top of the house someone built for Him. The closest I ever got was when I slept for seventeen hours and woke up after sunset.

I imagine the monastery on a hill, in the dark, the stone against the night sky, English wilderness sprawling out beneath it. The monks looked into the dark and glanced around feverishly for anyone to hear the discordant noise, to see what they saw, and in the miles around there was no one else there, only the screaming of white-faced barn owls, the scurrying of weasels beneath the warm earth, far below.

Their chronicler wrote it all down. Beneath the ink lurks the echo of the monks’ wild eyes, their flashing hands; they told him it “throbbed like a wounded snake.” Disdainful, he writes with a reluctant hand how the moon “writhed…in anxiety.” The letters sunk into the paper and five men returned to watch the sky, I suppose, but it must have felt hollow—maybe it left a bad taste in their mouth, maybe they left the tower and went to their cells, suffering moon stuck in their throats.

The other day I was talking to you, and unbidden came the thought that I wish I could become your friend all over again. I want to hug that realization so close to me, hold it up to the light, use it to decipher secret messages. I am so sure it means something. My horoscope told me that all friendship is romantic.

I spent the summer someplace else. I always do. I traced a new town with new friends, walked the small streets and lay on sloping, rolling grass. One afternoon, three of us went out to eat. We were the only ones there—the room was cold, empty glasses glinting on empty tables. We fingered the dim sum menu, a slip of white paper laid out with dishes, one after the other. We scratched in enough to heap the table with food. Our chopsticks clicked, and we shoved dough into our mouths and let soup leak onto the table. Friends come so easy to me now. It used to be that speaking was a spotlight lined with tripwires. Now I sell my own faulty wares like snake oil that really does cure cancer. I made my group of sweet, kind girls laugh with a wave of my hand. Behind my crinkled eyelids, I enumerated their faults.

There are these time bombs buried in my psyche—as if placed there, landmines lowered lovingly into the grave. Like an RGB display on the dome of my skull. Those monks, it’s long been thought that they were seeing the formation of the moon’s Giordano Bruno crater—named after a man burnt at the stake for insisting that the universe was infinite, that it had no center. But recent evidence suggests that the crater formed millions of years before the monks hurried down the steps of their monastery. It’s possible they were seeing a meteor burn up in the atmosphere, in perfect alignment with the tine of the moon. No one else on Earth recorded the event because they were the only ones who could have possibly seen it. Who would have seen the moon disintegrating instead of a corner of the sky combusting. A layer of thermal paste coats my ancient tongue when I think about them.

In spring, I sat next to you on the bench, eating pizza. You told me that you’d hooked up with your roommate when you were away; I slapped you for not telling me earlier. I slap a lot of people. You slapped me two years ago for stealing some of your food, so loud that everyone in the cafeteria turned to look at us, and we started crying and laughing. On that bench you were so shy and your smile was small and playful, and I want you to know that it looks good on you. How much you love me. How much you want me to know that you do.

And I want you to know that I am still a child, that there is so much I do not understand. I’m not talking about the innumerable facts still foreign, far-off windows: how bridges are built, why exactly leaves turn red in the fall. I mean the woman carrying a plastic takeout box down the street, the people in the shop window running their long fingers over lush coats, that man’s belt buckle, that girl’s bouncing purse. I do not know who they are.

R. S. Williams is a high school senior in New York. His poetry has been published in Prometheus Dreaming.

I found this poem as the top result for looking up a quote I can't find. The quote isn't from this, I don't know what it's from, but thank you for this passing gift that isn't mine. I love to collide with poetry and to have it collide with me. Thank you <3